By Henri Labayle, CDRE

The trees in the famous Billie Holiday song Strange Fruit stood out from others by the bodies hanging from them. Like those trees, the spotlight has been turned on the European Union’s asylum policy by little Aylan, a Syrian child found drowned on a Mediterranean beach. His death has given a face to the macabre thousands of deaths that came before his. His impact marks a shift in the existential crisis of the EU’s common asylum policy, at long last dragged to the only ground worthy of standing on—the European Union’s values.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel is the only leader to have made the EU’s values the crux of the debate, forcing her fellow leaders to choose a side and asking whether the Union can continue to remain indifferent.

To answer this question by examining the issues facing the EU, we must first define the situation (I). Once this has been clarified, we must then measure the scope of the current crisis (II) and the solutions the EU claims to provide (III).

I – Current assessment

The media frenzy over the flood of refugees seeking asylum in the European Union has been staggering. For months now, if not years, this long, hard battle has gathered pace to general public indifference, an attitude that has been carefully cultivated by leaders not wishing to reveal their indecision and exploited by extremist parties who ignore the lessons of history.

We must therefore consider some legal facts (b) and crunch the numbers available to us (a), an essential analysis in any public debate of this kind.

- The facts

The numbers are cruel. It seems odd that they have been so seldom analysed to measure the scope of the problem that Europe is facing. For several weeks now and especially since their publication in the European Commission’s agenda on migration, charts and graphs of asylum applications have abounded, often to bolster the argument that this flood of requests is unparalleled in history. But we cannot accept this conclusion at face value without first putting it into perspective.

We must make this first distinction clear: there is a massive trend, borne out by figures from late 2014 in Eurostat tables and European Asylum Support Office (EASO) reports, from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (HCR) and the European Migration Network (EMN) and backed up by national reports, including from France’s office for the protection of refugees and stateless persons (OFPRA). There are important lessons to be learned from these sources, as we will see later.

Added to that is another trend caused by an eruption in the crisis that had been simmering though ignored. This second trend is harder to pin down, as its extent has been measured only approximately since January 2015. In any event, it is plunging the EU into a situation already worse than the one provoked by the wars between former Yugoslavia and Kosovo, when hundreds of thousands of refugees fled the country, especially into Germany, for a lengthy stay before returning home.

This initial analysis is insufficient. It makes no sense to analyse current asylum applications unless we place them in the perspective with the current situation. To put it into the technocratic terms so beloved by our leaders, thinking in terms of flows means we must focus on stocks.

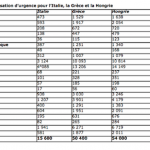

When tallying the numbers, one observation stood out as being abnormal: the EU has no way of measuring or comparing Member States’ actual actions so that it can make decisions based on objective truth. The weakness of the statistical tools available to government decision-makers is shocking, despite the quality of Eurostat’s work. Though regulation 862/2007 at long last imposed a requirement on Member States to provide the necessary information, statistical methods still fell short of expectations, whatever the EC might think (COM 2015 374). This is illustrated by the attached table listing the number of people receiving international protection in the EU, basic data that must be properly understood. Counts vary widely between reports from the government, the HCR, Eurostat, EASO, Frontex, and NGOs. It has also been impossible to obtain from Eurostat the exact number of refugees residing in the EU in 2014, despite the high quality of information provided.

There are several reasons for this: The situation is a complex one, national and European systems were designed differently, and states are reluctant to reveal their moral turpitude. Nevertheless, given the severity of the political crisis, a reliable assessment of the current situation is a prerequisite to government action, lest evaluations and presentations of the case for public opinion be distorted. Since such an assessment is unavailable, we should make just a few small additions to form “estimates” that, at the very least, reveal underlying trends.

For example, according to France’s OFPRA annual report (which may be the most reliable source), France took in 192,264 protected persons in 2014, 178,968 as refugees and 18,296 as asylum seekers. Eurostat reported only 144,451 such persons (133,316 and 11,135, respectively) since its counts do not include minors, and the HCR was the most generous of all, reporting a total of 252,264 protected persons in France.

However, even using the highest numbers from the HCR, actual asylum counts are no reason for feigned indignation and false promises of generosity, as we will see.

Again, France’s case sheds light on what is at stake in the current crisis. The country’s population is just over 66 million, around 4 million of which are immigrants. Of those, fewer than 200,000 received international protection in 2014 according to OFPRA. Public opinion would also benefit from a view of the breakdown of geographic provenance before making any judgement: 38% of immigrants were from Asia, 30% from Africa, and 28% from Europe. Within this subset of refugees, the largest groups were from Sri Lanka (13%), Congo (7.6%), Russia (7.2%), and Cambodia (6.9%). France is nothing like the “land of asylum” it claims to be, as can be seen in comparisons to Sweden. In 2014 alone, the 20,640 refugees received by France paled in comparison to Sweden’s 33,000 and Germany’s 47,555.

A table summarising the major trends observed in the West confirms these disparities, in particular between the European Union and the rest of the Western world.

The current state of asylum applications should be examined in light of these numbers, even if they are only approximations. In 2014 France received 68,500 applications for protection, 2.2% fewer than in 2013. It accepted 20,640 of cases. Accepting the EC’s current proposals would mean taking in 12,000 additional refugees per year for two years. The maths is simple: with 66 million people in France, four million foreigners, and 192,000 permanent refugees, an extra 12,000 Syrians in one year.

How does this increase translate into an invasion or unreasonable effort? In the 1970s, then-French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing received 130,000 Vietnamese and Cambodian refugees into the country with the broad, empathetic support of the intellectual and political spheres. The idea of accepting in 2014 one-tenth that number of refugees, people whose very lives are threatened, provokes reservations if not outright hostility towards such “boat people,” even though they come from much closer to home this time.

From the EU’s perspective the situation is more complex, as we have written here several times before. The situation deteriorated rapidly in 2014 at the height of the Syrian crisis, with asylum requests skyrocketing from 336,000 in 2012 to 626,715 in 2014. There were nearly as many applications in the first half of 2015 as in all of 2013 (432,060), a clear indication of the extreme gravity of the situation. More than 100,000 people arrived in Greece in July alone. Projections and analyses by various organisations from EASO to Frontex to the HCR all confirm the urgent need for a response.

Member States experience varying degrees of pressure depending on whether they are located along the exodus route or are a first stop for many refugees—and that is the crux of the problem. At the heart of the debate is Germany, which indisputably plays a determining role, both because it is the top choice of asylum seekers and because of the position it holds in the EU. Though it is unknown whether such evaluations are accurate, it is estimated that 800,000 people will arrive in Germany in 2015.

Unlike France, despite the exhilarating description published by the French Minister of the Interior in the daily Libération, and contrary to the United Kingdom’s head-in-sand response, Germany’s position contrasts with that of other countries. It consists simply of enforcing laws and treaties and abiding by Western values.

- The law

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, international protection is a right granted by both the constitution and treaties. It is a fundamental error to suggest that we pick and choose which asylum seekers to accept or to lump them in with “migrants.” Our acceptance of them is a legal obligation sanctioned by a judge. The EC is now paying the price for having conflated the two in a European Agenda publication, as we have mentioned before.

Not only is there a constitutional right to asylum, but at the international and European level, EU Member States are individually and collectively required to fulfil their duty and process applications for protection—firstly, because the Geneva Convention of 1951 on refugees prohibits them from doing otherwise, including by deporting refugees back to dangerous regions; secondly, because the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) forbids the same thing, a prohibition sanctioned by the European Court of Human Rights; and lastly, because the EU guarantees the right to asylum in article 18 of its Charter of Fundamental Rights and states in article 19 that “collective expulsions are prohibited” and that “no one may be removed, expelled or extradited to a State where there is a serious risk that he or she would be subjected to the death penalty, torture or other inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Unlike solutions designed for traditional immigration issues, when it comes to refuge and asylum, Member States’ sovereignty is significantly undermined by their weighty obligations, including their duty not to shift their problems to other countries, especially to countries outside the EU. The miracle solution is not to pass the buck.

In addition to assurances that they will not be deported, asylum seekers have the right to fair and efficient asylum procedures and assistance with basic living needs. With these mutual obligations in mind, Member States have adopted a common asylum system whose second generation of laws govern procedures, conditions of acceptance, and qualification rules. These topics are more or less addressed in regulation 2015-925 of July 29, 2015, which transposes these directives. Given such conditions, it is incongruous to call for a truly unified asylum policy as the French administration did in August.

As summer draws to a close, the disconnect between the facts and the law is striking—and fatal for its victims. It merits an explanation, if only a cursory one. The inability of one of the most advanced legislative chapters of EU law to rise to meet a real-life challenge is indeed surprising.

In the first place, Member States seem to have had a long-standing strategy of shifting responsibility for asylum applications. The misnamed Dublin Regulation, which inspired the Schengen application agreement, establishes a single procedure for processing asylum applications, which are generally handled by the Member State through which the applicant enters the European Union. This policy places an undue burden on Member States located on the outer border of the Schengen area but is highly convenient for members in the interior.

Whether impoverished, like Greece, or not, like Italy, under normal conditions countries fulfilled their roles one way or another—though not without taking some liberties with EU values, as Greece did regarding the handling of asylum seekers and as Italy did under Silvio Berlusconi, when it sent refugees back to Gaddafi’s Libya. The practices underlying these shoddy solutions were condemned by the ECHR and broke down completely in the geopolitical implosion that struck the Mediterranean area. The war in Iraq and Syria prevented the practices from becoming entrenched, and at the very least the non-paper (which we will come back to later) published by Federica Mogherini, High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, stated “Europe must protect refugees in need of protection in a humane way—regardless of which EU country they arrive in.”

This was undoubtedly Germany’s implicit message when it announced its decision to open its interior borders to asylum seekers coming through other Member States. Germany’s calm acceptance of its responsibility to protect refugees coming from other Member States in the Schengen area—or perhaps its demand for other Member States to do the same—is a scathing indictment of the Dublin system and its inadequacy in the face of a crisis of this scope.

Some months earlier, France’s attitude towards neighbouring Ventimiglia was radically different and lends some perspective to the hypocritical discourse now being put forth by the government. Faced with the same public opinion, France and Germany have arrived at different conclusions. Whereas Germans were swayed by a certain respect for values and the law, in France, political calculation, a lack of courage and contradictory discourses are the rule rather than the exception at both ends of the political spectrum. And all for naught, for in politics as in football, Germany always wins.

While we will not list all of the flaws of European asylum law here, there are two gaping holes that deserve mentioning.

The first is general and has to do with the lack of serious consideration for external factors in the common asylum policy. The policy is political in the earliest sense of the word, as it was used in Antiquity when churches provided asylum, implying a stance taken against the persecutor. The stance itself is also flawed in application, if not in what is said, regarding both the Syrian regime and the rebels fighting it. The EU is current in an impasse brought on by Germany’s silence, France’s changing positions, Britain’s caution, and the cowardice of others, including some Member States who refuse to get involved, claiming they were not the ones who invaded Afghanistan or Iraq.

The failure of the EU’s foreign policies and that of its members is therefore a pressing issue. Protected persons live, by definition, in a precarious position. Should the threat to them disappear, the protection afforded them automatically disappears with it. It is surprising that no one has pointed this out. The war in the Middle East, especially in Syria, has been the main source of the flood of refugees; ending the war would likely reverse the flow and allow them to return. Focusing attention on the deportation of illegal immigrants without discussing displaced refugees is not good politics, except to consider that a new Palestine is being formed in Iraq (which has 250,000 refugees), Lebanon (1,113,000 refugees), Jordan (630,000 refugees) and Turkey (2 million refugees).

One condition of effectiveness, then, is a solution to the root cause of the problem, as lobbied for by advocates of intervention, and a fix for the region of conflict. The deafening silence from the EU and its members on the topic is troubling, including and especially in Berlin. The timidity with which Ms. Mogherini’s non-paper broaches the matter explains the polite silence with which German, Italian and French ministers have acknowledged it.

The second flaw of European asylum law is more specific to asylum and the current crisis. The thousands of deaths in the Mediterranean—more than 3,000 according to the HCR—and en route to the Balkans begs a central question regarding the infrastructure of the current asylum policy and its lack of a legal path for protection seekers. Such a path would give refugees an alternative to risking their lives for what is, after all, a right, the right to have their application examined. Asylum seekers in Syria requesting protection in France should not be rejected by the French government under article 21 of the Schengen Visa Code due to their inability to prove they can return to their home country.

In other words, the EU is at the end of a long process during which it claimed to have formed a common policy but left its application to Member States, in particular those on the border of the Union. The current crisis has now led the EU to clearly present the debate in terms of national and intergovernmental withdrawal, thus bidding farewell to the Area of Freedom, or of any advancement in a pre-federal way by sharing duties and responsibilities, especially and including through executive agencies tasked with overseeing asylum seekers.

It is the telling effect of a deep internal crisis.

II – State of crisis

The crisis currently affecting the European Union’s common asylum policy erupted the day after the European agenda on migration (COM (2015) 240) was published. Both a moral and institutional issue, the crisis is in reality much larger than commonly believed, with roots that run deep.

- A moral crisis

The disappointment following the Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) Council meeting on July 20 triggered an open crisis, which was exacerbated by the bloody exodus occurring in the Mediterranean at the time. With regular leaders away for the summer, the EU’s institutions quietly gave way to national egotism.

The Council agreed to assist Italy and Greece by “relocating” 40,000 people clearly in need of international protection. A draft decision by the Council provided for assistance in the form of a “temporary and exceptional mechanism.” This “voluntary” position fell short of the desire of Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the European Commission, to apply pressure to the situation. Juncker bluntly criticized the EU for its ineffectiveness.

A “resolution by representatives of Member-State governments meeting in the Council” addressed this partial failure, incapable as it was to reach the proposed symbolic number of 40,000 refugees. The refusal, out of petty solidarity, by certain Member States to cooperate kept the count at 32,256 “relocatable” persons coming from Italy and Greece. The promise to reach the goal by December 2015 was not enough to relieve the migratory pressure, nor enough to unite the EU in action, a failure that revealed some worrisome fault lines.

A front formed of countries refusing to cooperate, members of which could easily be guessed by reading Eurostat’s statistics on asylum applications and acceptance rates. Indeed, the story is illustrated by the number of applications accepted by each country. Poland grudgingly accepted 720 refugees in 2014, and the Baltic States trailed even further behind (20 for Estonia, 25 for Latvia, and 75 for Lithuania). The Czech Republic accepted 765 refugees, Slovenia 45, and Spain 1,585. Uniquely among them, Hungary turned the matter into a political issue.

Comparing those numbers to swamped Bulgaria’s 7,020 refugees, Belgium’s 8,045, and Sweden’s 30,650 led to an impasse in early summer.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel courageously took up the mantle in mid-August, alone in the face of a silence emanating from France that belied the dithering of its leaders. Her forceful step took two forms, both significant. In a highly political move to begin—and, one might add, end—with, Germany framed the issue as an urgent one that should be broached first and foremost from the viewpoint of the principles and values underpinning EU ideals. Merkel also deliberately accentuated the crisis and suggested that the inability to resolve the issue may pose a threat to freedom of movement within the EU.

This is the ground on which the issue is based. The EU’s values, in particular regarding asylum, have become but empty words. Though much discussed by national politicians, many Member States deliberately refuse to fulfil their duties. The common policy has become to ignore the impetus behind the mass exodus, caused by a lack of a common foreign policy; to look the other way when neighbouring States, from Turkey to Libya, are complicit in persecutions; to ignore States’ failure to control EU borders or receive refugee applicants; and finally, to refuse to combat that modern form of slavery that is human trafficking.

Merkel’s stance revealed Member States’ true colours and amplified the opposition separating them on the issue of migratory policy and, more specifically, on exercising the right to asylum. As Merkel stated to the Bundestag, the EU and its members have not learned from past lessons. To be precise, the current issues are the initial ambiguity as regards border control, the presence of immigrants from non-EU countries, and the asylum policies that accompanied the EU’s eastern expansion and that were never clarified.

In mid-summer, the shift of migration paths from the Mediterranean to Central Europe and the Balkans brought things to a head. The meaning and scope of certain treaty terms remain unclear for a non-negligible portion of Member States, particularly the terms “values” in articles 2 and 3 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and “solidarity” in articles 67 and 80 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

Although these Member States are well aware of the migration phenomenon, either because their own people migrate towards the Western part of the Union or because they receive migrants from the East—notably from Ukraine and Russia—the cultural gap created by their national histories has not been bridged. Whether the issue was controlling external borders, which have been invaded by others for half a century, or international protection in the name of fundamental rights largely unknown in their own culture, the debate remained more or less theoretical at the internal and governmental levels. The trigger was the transition from theory to application provoked by the July crisis, once the question was no longer one of receiving EU money for pre-accession and for bolstering JHA instruments, and especially since the countries themselves were disallowed by other members from joining the Schengen area for seven years.

Hostile—if not outright radically opposed, as Hungary is—to any sort of solidarity between states on matters they feel do not concern them, these States have stepped up their shows of defiance, forming the so-called Visegrad group. The group is led by Hungary and has been joined by the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia and quietly supported by the Baltic States and Spain. Backed into a corner, they have expressed opinions and adopted behaviour that express doubt as to whether they will agree to any project or common values whatsoever. Signs of their defiance include the fear of an “invasion,” talk of a “Christian identity” (both fuelled by the media’s coverage of the crisis), the building of “walls” and the behaviour of law enforcement on the ground. The group’s meeting on September 4 ended with a firm refusal to shoulder a portion of the responsibility, a compromise deemed “unacceptable” by all members. Hungary even declared that the issue was exclusively “a German problem.”

At the same time, the end of the summer saw a resurgence in migratory tensions at the French-British border, with Calais and the Eurostar terminal succeeding Sangatte. In addition to the peculiarity of seeing France protect the borders of a country outside of the Schengen area and receive financial aid from the EC for doing so, the British administration’s opportunity to distinguish itself from the EU’s policy and the Schengen measures, which it nevertheless benefits from, was too good to refrain from criticizing them and finding justification in it for its opting out.

Thus in the face of divided Member States, Germany’s explicit threat to re-examine the functioning, if not the very existence, of the Schengen area must be taken seriously. The Schengen system was designed for peacetime but is collapsing under a major crisis, with questions both of entering the area, from the Balkans to the South, and of leaving it, as in Calais. Some of its main principles, including the Dublin method of processing applications, may not survive the crisis, if one is to believe the letter from the ministers of foreign affairs to their EU counterparts. However, finding a resolution requires an effective institutional system not mired in its own crisis. Courageously, Luxembourg’s administration is calling for a “top-down” solution to the crisis.

- An institutional crisis

The EC’s proposal this past spring to apportion out asylum responsibilities has reached an impasse, both in terms of both its non-obligatory nature and its numerical targets. The EU’s refusal to face the migration question and the ongoing conflicts at its borders made the proposal impossible.

With some difficulty, a majority of Member States was made to unite behind Juncker’s brave initiative. The grudging agreement, the ultimate insult for a supposed “common policy,” took the form of a reasonably intergovernmental “resolution of the representatives of the governments meeting within the Council,” the same attitude as for the relocation issue. These events are further proof of the EC’s powerlessness to force States to open their doors and the European Parliament’s complete inability to serve as the counterweight that was hoped for when the material was submitted to the qualified majority.

The legal debate over the EC’s proposal deserves a mention here, even though it was quickly sidestepped in the European Parliament during the proposal’s vote on September 9.

The proposal presented by the EC would instate temporary (24 months) measures to assist Italy and Greece in matters of international protection and would imply a moratorium on Dublin regulation 604/2013. As a legal basis, the EC cited “an urgent situation characterised by a sudden inflow of nationals of third countries” justifying “the adoption of provisional measures” as stated in article 78.3 of the TFEU and requiring a simple consultation with Parliament.

However, article 78, paragraph 2, item c) of the TFEU cites “temporary protection…in the event of a massive inflow” as a factor in a common asylum system and places it under ordinary legislative procedure.

The matter would have been debated if the decline in the situation hadn’t caused timorous European parliamentarians to seek to avoid a legal battle, at the risk of losing their positions as co-legislators. Indeed, the “urgent situation” and “sudden” character of the inflow of applicants could not have gone unnoticed in May 2015 by EU institutions and its members. For many months, everyone from councils of ministers to European councils filled the news with commentary on the devastating litany of deaths in the Mediterranean, a scandal that provoked recurring internal crises in the EU, for example during the Arab Spring. Statistics from 2014 produced opportunely by Eurostat indeed confirm that the EU’s inaction was a greater force behind the backlash in July than any unforeseen event in the first half of 2015.

Aware it could not win a losing battle, Parliament passed a resolution approving the initiative, though it noted that it could “accept article 78, paragraph 3 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union as a legal basis only as an emergency measure, which will be followed by a proper legislative proposal to structurally deal with any future emergency situations.”

The quagmire in which the EC found itself at the beginning of the summer, before Juncker’s offensive in his general speech on September 9 on the state of the European Union, was joined by a harsh questioning of its ability to fulfil its duties regarding the migration question.

Here again the German administration was at the ready, pointing out the slow application of the decisions and the curious impunity with which some states, from Greece to Hungary to Italy, were allowed to shirk their duty of transposing and applying the common laws. The criticism was largely well founded, both for the snail’s pace at which the decisions were to be implemented and for the system of verifying that the EU’s asylum and immigration legislation is being applied, a system that falls exclusively to the EC.

The critiques are distinct yet are both accurate. Besides the technocratic slowness at which even the smallest decision is implemented, there is a note of defiance in internal relations within the Schengen area. The suspicion by final-destination States that first-stop States are failing in their duties of verifying, receiving, and registering refugees is not without merit. From Hungary’s attitude to Greece’s helplessness to Italy’s ambiguity, there is much to address, especially when considering the transposition and application of secondary legislation. It becomes patently obvious that the previous patchwork remains in place.

Juncker is perfectly aware of the state of things and is churning out proof of his good intentions, including by announcing that proceedings have begun on 32 cases of infringement of the so-called Asylum Package, though this step is less impressive when the highly formalistic nature of these procedures is known. The quite ingenious publication on the day of the President’s speech of an advertisement casting his actions in a positive light was barely enough to drown out the mounting criticism. The stakes in this case are high; if States do seize power, as suggested by Germany’s leaders, the EC will be relegated to playing a mere supporting role. Have protagonists forgotten so quickly the recent spats over the AFSJ evaluation in the Schengen area?

The third source of institutional disruption, the position of the European Council’s president, is more anecdotal—except given his supposed role following the Treaty of Lisbon.

Faced with a crisis in which his national loyalties clearly took precedence over the importance of his title, Donald Tusk saw fit in early summer to hinder the EC’s initiative by focusing on deporting rather than receiving asylum seekers. A far cry from the “honest broker” his predecessor tried to be, Tusk instead had a hand in the proposal’s failure. To hear him three months later at an annual conference of EU ambassadors defending a proposal to triple the number of refugees in the EU in the name of its values leaves audiences wondering what value exactly the European Council adds.

Juncker’s discourse and his reaction to the worsening crisis were then eagerly awaited to outline a route out of the crisis.

III – A way out of the crisis?

Jean-Claude Juncker’s discourse on September 9 on the state of the European Union had the merit of capturing the ground first cleared by the Federal Republic of Germany and later by France. In a rousing speech free of finger-wagging, the European Commission president invoked the past and heritage of all EU members to encourage the adoption of his legislative plan.

The increased refugee relocation quotas drew the most attention for their distribution of responsibilities across the board, but several other points in his speech also deserve examination. We will address those here later.

- Confirmation of an emergency relocation mechanism

Obviously and in light of the events at the end of the summer, the relocation of people reaching the EU remained the priority topic, both to clear the caseload of applications submitted in July and to pave the way for the future.

It was imperative to provide an emergency response to a humanitarian situation that had become untenable in the central and southern parts of the EU. The crisis demonstrated the near-impossibility of opposing such a wave of people in a democratic manner while also using police tactics.

The route taken by the EC’s proposal for aiding Italy and Greece was not an easy one, and though Juncker was rightfully disappointed by his initiative’s fate, at the very least the topic of relocation launched two other debates, on the inadequacy of the Dublin system and on the quota system for asylum seekers.

The proposal for asylum-seeker quotas progressed only with great difficulty and provoked opposition on principle, including from the French administration, and a rejection of all quotas from a non-negligible number of Member States, particularly in the east.

But there was another possibility that flew so far under the radar a former president of France believed a “war refugee” status could be created. This in turn gave the Minister of the Interior and the Prime Minister a political opportunity to claim that a new status was impossible due to the “indivisible nature” of the right to asylum. Such ignorance by all three politicians of directive 2001/55 of July 20, 2001, transposed in 2003, could have been avoided simply by reading its heading—“on minimum standards for giving temporary protection in the event of a mass influx of displaced persons and on measures promoting a balance of efforts between Member States in receiving such persons and bearing the consequences thereof”—which demonstrates that the directive may be applied in this case.

The directive was inspired by the 1992 Balkans crisis, when nearly 200,000 people sought refuge in Germany, and applied to the 100,000 Kosovars it protected. In today’s situation, the advantages of invoking the directive would be significant, especially to assure a reticent public that the protection would be “temporary” (one to three years), even though the rights it grants are lesser than those for normal asylum status, and despite the fact that in the current migration wave, it would be difficult to make a special case for Syrians over other nationalities affected by relocation.

It would therefore be reasonable to believe that the difficulty of swaying Member States, their refusal to publicly acknowledge the disparity of their responses to Syrian refugees, and the lack of a proper, communal system are all the result of the EC’s preference for a different solution.

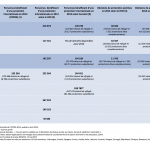

Filed on May 27, 2015, under conditions already described, the Council’s draft decision COM (2015) 286 and its appendices took the form of a draft decision approved by a resolution by representatives of Member State governments. The measure consisted of a temporary derogation of article 13 §1 of regulation 604/2013, under which Italy and Greece would otherwise be responsible for processing applications for international protection. This was its secondary advantage.

The Dublin system’s inability to handle a large wave of applicants indisputably called into question the survival of a regulation that makes first-stop countries responsible for protection seekers. For structural reasons, Greece was long unable to fulfil this duty, to the point that it has been criticised for it by the ECHR, in vain. In brief but repeated episodes, from the Arab Spring to the various dramas in Lampedusa, Italy fared no better. And when the pressure became too much to bear, Hungary and its neighbours demonstrated the same shortcomings.

Since EU Member States on the “front lines” were no longer able to abide by Dublin regulations, the consequences had to be faced, and States could no longer ignore the problem, either legally or practically.

In fact, Germany, Austria and others concretely recognised that the community was powerless by opening their borders to applicants. But this understanding should not be taken as a rejection of the Dublin system; Dublin’s sovereignty clause allows any Member State to open its borders, and there are no refugee rights allowing applicants to freely choose their destination. This was borne out by Germany’s decision to re-establish border controls on September 13.

Legally then, all mechanisms for receiving refugees instated since July, both for relocation and resettlement, appear to comply with the Dublin system, with the derogation they propose motivated by the urgency of the situation. All are accompanied by a proposal—which we will come back to later—to amend Dublin regulation COM (2015) 450 establishing a permanent mechanism for relocation in the event of a crisis.

- Contents of the emergency relocation mechanism

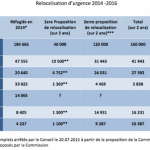

The first draft decision put forth to the JHA Council targeted applicants with asylum acceptance rates greater than 75%, mainly Syrians and Eritreans according to Eurostat figures. Article 4 of the draft decision regulates “relocation of applicants in Member States” by distributing the total number by 40,000 people over two years, mainly in Italy (60% or 24,000 applicants) and Greece (40% or 16,000 applicants), in application of the “equitable sharing” agreed to by the other Member States. We have seen how this plan failed, since negotiations were unable to achieve figures higher than 32,256 people, as the European Parliament stated on September 10.

The text was not terribly enlightening, but two of its characteristics deserve mentioning.

The first concerns the extreme distrust, to put it mildly, shown towards Member States benefitting from the mechanism. Their shortcomings described above explain the clearly expressed desire to force them into effectiveness in exchange for taking on some of their responsibilities. The deadlines stipulated in the text include “operational support” to both States described in article 7, along with “additional measures” of a structural nature, including a “roadmap” required by article 8 §1, which if not followed will cause the mechanism to be suspended. Implementing the text will have a non-negligible impact on States’ sovereign decisions in terms of operations, especially the highly praised “hotspots.”

The text’s second point touched on the great disdain with which applicants continue to be viewed. All applicants are well aware that they have little say in where they are relocated. The Achilles’ heel of Europe’s asylum policy is the concern over the “secondary migration” of applicants, a topic clearly at the forefront of minds, and for good reason. Despite the Dublin system, which attempted to keep applicants in their first-stop countries, the largely insufficient conditions in the two main receiving States—Italy and Greece—only spurred applicants to move on to Member States where they believed, rightfully or not, they could rebuild their lives; these included Sweden, Germany and, to a lesser extent, the UK. The lower attraction of some Member States, such as France, explains those countries’ difficulty in finding asylum applicants. But forcing relocated persons to stay in the State assigned to them will not be a simple task.

In addition to traditional reservations for reasons of public order within the State of relocation, the draft decision also states that applicants will be informed that, if they attempt to cross borders illegally at a later date, in principle they may only benefit from protection rights granted by the Member State to which they were relocated while within that State. For the same reasons, applicants may be summoned to appear before authorities and may only receive material aid in kind, to prevent financial incentives.

It remains to be seen how the proposal, which received approval from the European Parliament on September 9 and from the Committee of Permanent Representatives the following day, will fare in the Council of Ministers on September 14.

The EU’s initiative was not enough to contain the exodus. Even before the first decision was taken, the initiative was largely insufficient given the situation: over 210,000 refugees in Greece, 145,000 in Hungary, and 115,000 in Italy. In addition to the pressure from the Mediterranean basin, the route to the Balkans put an unbearable strain on third States, for instance Serbia and Macedonia, and Member States, such as Hungary, which experienced a 1,295% increase in applications in 2015.

A second proposal was announced at the state of the European Union speech, while the first proposal was still being passed. The main unique provision in the new proposal was the addition of Hungary to Italy and Greece and an increase in the number of relocations to 120,000 people—which, when combined with the original number, totals 160,000 people relocated in two years.

Employing criteria used in July to evaluate Member States’ hosting capacity (40% for population size and GDP, 10% for the unemployment rate and the average number of asylum applications in the last four years, with upper limits of 30% for the latter two to prevent a threshold effect), the EC is proposing a distribution that will cause significant changes for some States, such as Spain and Portugal.

We will be able to revisit these mechanisms in more detail, here and later, if only to lament the focus on current asylum applications instead of the refugees already under protection, a viewpoint that would have provided a more accurate snapshot of States’ efforts.

For now, on the eve of the Council of Ministers meeting on September 14, we will list only a few outstanding questions.

The first regards the technical incongruity of how Member States arrived at their figures. Transparency is entirely impossible if the relocation decision is disconnected from its enforcement numbers. One was the product of article 78 §3, while the other was decided “by consensus” in the form of an appendix to a resolution by Member State representatives. The former was shaped by the need to at least “consult” the Parliament, while the latter was left entirely up to the States and calculated in complete opacity, since it lay outside of community procedures, as did the fulfilment of promises made.

The second curiosity has to do with the appearance, on September 9 in article 4 §2 of the draft decision, of a “temporary solidarity clause” that was surprising to say the least, a polite way of calling scandalous the monetisation of observing a fundamental obligation. By providing justification compatible with EU values enshrined in article 2 of the TEU, a State may “in exceptional circumstances” notify the EC that it is temporarily unable to participate, in part or in whole, in the resettlement of applicants for one year. Under the EC’s watchful eye, the State may then make a financial contribution of 0.002% of GDP to the EU’s budget to fund the efforts of other Member States to respond to the crisis. Citing the example of a “natural disaster”, the EC will likely have trouble convincing audiences of the seriousness of this option.

More generally, the current legislative process, so courageously led by Juncker and the president of Luxembourg, is clashing with reality. The spectacle of Danish, Austrian and Hungarian railway stations, trains and motorways, together with the public opinion—even in Germany—of applicants illustrate the disconnect with reality, even for opt-out States like Ireland and the UK.

In reality relocation is already happening, if we consider the difficulty of reversing course and if we acknowledge the influx it has created. The plodding procedures of institutions, the trench warfare conducted by chancelleries, and the technocratic management of decisions are all striking, considering what is at stake. Both proposals are meant to apply to people who arrived in Italy and Greece “one month before the publication” of both texts. But what about other applicants of the same provenance?

In other words, Juncker’s redirection of the flow of asylum seekers has every likelihood of producing, for many seasons to come, what Billie Holiday called “a bitter crop.”